Pressure Drop Models and Correlations

The steady state pressure gradient along a flow line can be expressed as the sum of pressure loss due to change in elevation, pressure drop due to friction and pressure drop due to change in kinetic energy. The first term (pressure drop due to change in elevation) is normally the predominant term in wells (except in horizontal wells) and can contribute from 80 - 95% of the pressure gradient. The second term (friction) normally represents 15-20% of the total pressure drop. The last term results from the change in velocity of the fluid which in most steady state situations is negligible. It can become significant however, in the presence of a compressible phase (gas) at low pressures as could be encountered in gas lift wells near the surface.

Determination of the frictional pressure loss require the determination of the friction factor, which is a function of the Reynold's number in laminar flow (Re < 2000) and of Reynold's number and the pipe roughness in turbulent flow (Re > 3000). Reynold's number is expressed as:

For turbulent flow however, the determination of the friction factor is not straight forward. The Colebrook equation is widely used to estimate the friction factor for turbulent flow:

Single Phase flow

The three components are relatively simple to compute as average properties are easy enough to calculate. The flow path is segmented, with each segment assumed to be at constant pressure and temperature i.e. constant fluid properties. The three pressure drop components are easily calculated. The total pressure drop is an integration of the segment pressure drops.

2 phase flow

When two or more phases flow simultaneously in flow lines, the flow behavior is more complex than that for single phase. The phases tend to separate because of difference in their densities. As a result, phases do not travel at the same velocity, with lighter fluids travelling faster in upward flow. Due to the varying speeds, phases occupy parts of the cross section (hold up) that is not the same as their volumetric flow rates. To estimate mixture density and viscosity, it is therefore important to predict the slippage velocity/hold up of each phase.

3 Phase flow

Two approaches exists to resolve the 3 phase problem - treat the three phases simultaneously or treat the three phase system as a combination of two 2 phase systems.

In the next sections, a brief description and theory of each available flow correlation in K-A:

Stanford Drift Flux

The Drift-flux models represent multiphase flow in wellbores or pipes in terms of a number of empirically determined parameters. The great advantage of this model is that there is a continuity between the various flow regimes.

The basic output of the model is the velocity/hold up of each phase. Once known, the hold ups can be used to determine the average segment fluid properties which can then determine the frictional, hydrostatic and acceleration components of the pressure drop.

Three variants of the model are offered: Liquid-gas, Liquid-liquid, 3-Phases.

The model divides a 3-phase system in to a liquid-gas system first to determine gas and liquid hold ups. Once the liquid hold up is determined, the oil-water system is resolved to determine oil and water hold ups.

2-Phase Liquid-Gas

The gas velocity is related to the mixture velocity by the equation:

Where C and vd are the profile parameter and the drift velocity respectively. Correlations exist for the determination of each.

2-Phase Liquid-Liquid

The oil velocity is related to the mixture velocity by the equation:

Where C' and v'd are the profile parameter and the drift velocity respectively. Correlations exist for the determination of each.

3-Phase Model

To model three-phase flow, a two-stage approach is first applied based purely on the two-phase flow models. The system is first treated as a gas-liquid flow to determine the gas hold up and then model the liquid as an oil-water system to determine the liquid hold ups. To account for the affect of gas on the oil-water slippage for deviated wells however, the model uses different coefficients for the empirical correlations compared to the 2-phase models.

Hagedorn and Brown

In 1965, Hagedorn and Brown published a correlation for calculating pressure gradients in wells flowing multiphase fluids. The correlation was developed from 475 tests obtained from a 1,500-ft test well at Dallas, Texas, along with 106 tests reported by Fancher and Brown. The combined data resulted in 2,905 pressure measurements. The test well used by Hagedorn and Brown was completed with two separate casing annuli to allow the injection of gas through a gas lift valve near 1,400-ft and liquid through the bottom of the tubing string. Pressure readings were obtained at four points along the tubing string using surface readout gauges mounted on the tubing. Temperature throughout the well was constant at 80°F. The ranges of the data are:

Tubing ID, inches | 1.049 | 1.380 | 1.610 |

Oil rate, STBPD | 0 | 0 - 960 | 0 - 731 |

Water rate, STBPD | 52.9 - 143.7 | 0 - 975 | 0 - 1.45 |

Gas-liquid ratio, SCF/STB | 101.3 - 2,350 | 21.2 - 3,460 | 24.6 - 5,030 |

Well depth, feet | 1,428 | 994 - 1,414 | 918 - 1,347 |

Wellhead pressure, psia | 35 - 117 | 28 - 115 | 33 - 119 |

Bottom hole pressure, psia | 222 - 383 | 124 - 417 | 104 - 373 |

tank oil gravity, °API | N/A | 26 - 34 | 31 |

Water specific gravity | 1 | ||

Gas gravity (air = 1) | 1 | ||

Surface tension, dynes/cm, Oil | 33.5 - 36.2 | ||

Surface tension, dynes/cm, Water | 72 | ||

Viscosity, cp, Oil | 10 - 110 | ||

Viscosity, cp, Water | 0.86 | ||

No flow-map was developed. The heart of the method is the single liquid holdup correlation provided for all conditions.

Since the original Hagedorn and Brown correlation was published, several modifications have been proposed. Among these include a restriction limiting the liquid holdup to values greater than the no-slip holdup, and the inclusion of the Griffith and Wallis correlation for the bubble flow regime. This can be activated by checking the Bubble flow add-on option for the correlation. The Hagedorn-Brown method is seen to over predict the pressure loss for heavier oils (13-25 °API) and under predict the pressure profile for lighter oils (40-56 °API). The pressure drop is over predicted for GLR greater than 5000. Pressure drop has also been observed to be over predicted for tubing sizes greater than 1.5 in.

Reference: "Experimental Study of Pressure Gradients Occurring During Continuous Two-Phase Flow in Small Diameter Vertical Conduits", Hagedorn, A.R., & Brown, K.E., JPT (April 1965), Vol. 17, p. 475.

"Two-Phase Slug Flow", Griffith, P. and Wallis, G.B., J. Heat Transfer; Trans. ASME (Aug. 1961) 307-320.

Beggs - Brill

As an attempt to provide an explicit relation to estimate z-factor, Beggs and Brill presented a closed form expression. The method adopted an empirical/explicit approach and the correlation is commonly recognized to be of a relatively lower accuracy, except at moderate pressures and temperatures.

Beggs and Brill reported using 94 data points in the development of the correlation which can only be used in the following range

Reduced Pressure | 0 - 10 |

Reduced Temperature | 1.2 - 2.4 |

Beggs and Brill reported and average absolute error of 0.19%.

Reference: “Two-Phase Flow in Pipes”, Brill, J. P. and Beggs, H. D., U of Tulsa, INTERCOMP Course, The Hague, Tulsa, OK (1974)

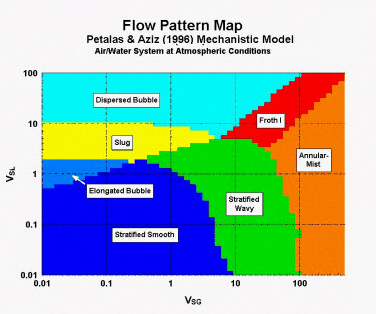

Petalas and Aziz

The Petalas and Aziz mechanistic model was not built for a specific set of data or fluid properties. Instead, the authors applied first principles to the possible flow patterns that can be observed at different inclinations. For this reason, it is applicable to any pipe inclination and fluid properties. The model was developed using subsets of a database of over 20,000 laboratory measurements and data from approximately 1,800 wells.

The model distinguishes the following regimes:

Elongated bubbles

Bubble

Stratified smooth

Stratified wavy

Slug

Annular-Mist

Dispersed bubble

Froth (transition between dispersed bubble and annular-mist).

Froth II (transition between slug flow and annular-mist).

Stratified flow regimes are restricted to horizontal flow.

The method could be summarized as follows:

Assume the existence of a flow pattern

Evaluate if this flow pattern is stable:

If the check fails, go back and select another flow pattern

If stable conditions are met, go ahead with the calculation of liquid holdup and friction factor

Calculate pressure losses using the found values for friction factor and liquid holdup

With the continuous evaluation of the stability of the flow patterns, the corresponding flow pattern map to the given flowing conditions can be created. The following is a typical flow pattern map for vertical upward gas-oil flow:

|

Reference: "Development and Testing of a New Mechanistic Model for Multiphase Flow in Pipes ", Petalas N., and Aziz, K., ASME Fluids Engineering Division Second International Symposium on Numerical Methods for Multiphase Flows, San Diego, Cal., July 7-11, 1996.

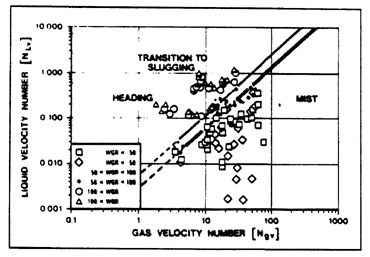

Reinicke et al.

In 1984, Reinicke, et al published a method for calculating pressure gradients in high-water cut gas wells. They initiated a study to determine a method for calculating the pressure drop for wells completed in the Rotliegendes gas formation in Germany. The study arrived at the following conclusions concerning multiphase flow correlations:

Correlations which do not use flow pattern maps under-predicted pressure drop but provided better results.

Correlations which use flow pattern maps significantly over-predict the pressure drop in high water cut gas wells.

Mist flow correlations yielded accurate results for a wider range of flow parameters than defined by the flow pattern map.

A total of 70 tests from 26 wells encompassing the following ranges were used in the study.

Well depth, ft | 10,082 - 16207 |

Nominal tubing diameter, in | 2-7/8 - 7 |

Flow rate, MCFD | 448 - 44980 |

Water-gas ratio, BBL/MMCF | 0.7 - 130 |

Bottomhole pressure, psi | 2,335 - 8905 |

Bottomhole temperature, °F | 214 - 315 |

Wellhead pressure, psi | 1,175 - 6991 |

Wellhead temperature, °F | 59 - 223 |

Gas gravity, (air=1) | 0.63 - 0.8 |

Water specific gravity | 1.00 - 1.24 |

The data was grouped into mist flow, possible mist flow and non-mist flow. A hybrid correlation involving the Duns and Ros mist flow model and Gray's correlation resulted. The following graph shows the flow pattern map used to define the slug-transition-mist flow regimes:

|

Since this correlation was developed using field data acquired from wells in mist or near-mist flow conditions, it is not expected to work well for wells in the bubble-slug flow regimes.

Reference: "Comparison of Measured and Predicted Pressure Drops in Tubing for High-Water-Cut Gas Wells", Reinicke, K. M., Remer, R. J. and Hueni, G., SPE 13279.

Gray

Gray's correlation was published in 1978 as part of the API computer program for sizing subsurface safety valves. The method was developed from 108 selected gas well tests of which 88 reportedly produced free liquids. Since the correlation was primarily developed for vertical gas-condensate wells, it usually predicts smaller values of liquid holdup than the other pressure gradient correlations. As a result of limits in the well data used for developing the correlation, Gray pointed out that it should be used with caution for the following conditions:

tubing strings larger than 3-1/2 inches nominal diameter

flow velocities above 50 ft/s

CGR above 50 bbl/MMCF

WGR above 5 bbl/MMCF.

Despite these restrictions however, the correlation has been successfully used with oil wells.

Reference: "Vertical Flow Correlation - Gas Wells", Gray, H. E., User Manual for API 14B, SSCSV Sizing Computer Program, App. B (Jan 1978) 38-41.